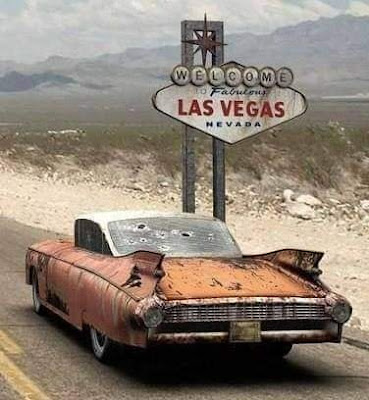

Trouble ahead, trouble behind…

Now go home…

Note: This post will make a lot more sense if you read Part Two first -- and reading Part One will bring you right up to speed...

It didn’t take long for our luck to turn. An hour out of Sun Valley, the windshield on the five-ton suddenly cracked for no apparent reason, startling the hell out of us with a jagged four foot crease across our field of view. A bad omen, that -- and sure enough, thirty minutes later an Idaho State Police cruiser was on our tail, red-white-and-blue lights flashing. Two cops -- one a tall, older veteran, the other a short, stocky kid who looked like he’d just joined the force -- wanted to see my license and the truck’s registration. I retrieved the license from my wallet, but the registration proved harder to find. It wasn’t taped to the inside of the windshield nor tucked in the glove box... but checking the latter was a tricky proposition thanks to the half-empty fifth of Jack Daniels and small baggie containing half a dozen White Crosses stashed therein.

Strictly for medicinal purposes, you understand -- fuel for the long drive ahead.

I kept searching while my buddy chatted with the cops, but those registration papers were nowhere to be found -- and now the tall cop was asking if we’d pulled over at any of the weigh stations.

Weigh stations? Hell, we’d blown right past everything that wasn’t a McDonalds, a liquor store or a gas station ever since leaving Las Vegas. Besides, we’d done most of our traveling at night, when the weigh stations appeared to be closed -- and I say “appeared” because we’d seen every one of those signs for weigh stations, but ignored them out of convenience, a sense of mission, and the fact that we were carrying substances frowned upon by law enforcement.

I played dumb (hardly a stretch, at that point), explaining that we had no idea a little five ton truck was supposed to stop at weigh stations.

"Those are just for big semis, aren't they?" I asked.

The older trooper shook his head, but seemed to buy our dumb-and-dumber act, deducing that he was dealing with a couple of doofuses too clueless to be real criminals, who thus posed no threat to the good citizens of Idaho -- and the sooner we exited his fair state of famous potatoes, the better. It seemed to help when we explained that the TV special we’d worked on starred Anita Bryant, who had recently created quite a stir in the national news for her public statements critical of gay people.

Hell, we couldn’t be all bad if we were making a TV show with Anita Bryant, could we?

The junior trooper had been quiet until now, but his body language -- arms crossed, and a cold, suspicious stare -- made it clear that he didn’t think much of us. At just over five feet tall, he was apparently afflicted with SMPD -- Short Man Personality Disorder.

“What do you for fun down there in LA?” he asked, an edge in his voice.

“The usual stuff,” I shrugged. “Go to clubs, listen to music, meet girls. You know.”

He glared at me for a very long moment.

“I wouldn’t live there for NUTHIN!” he barked, nearly coming out of his shoes on that last word.

Okay...

The older trooper saw the situation veering the wrong way, and had better things to do than spend the rest of his day taking us in, impounding the truck, then filling out reams of paperwork.

“You boys go on your way,” he said, “but be sure to stop at the next weigh station, understand?”

“Yes sir,” we nodded, then climbed back in the truck without another another word.

That little cop had freaked me out, but in retrospect he did us favor -- it was his outburst and obvious lack of self-control that convinced the older trooper to let us go, despite the fact that we had no papers for the truck.

I fully intended to follow his orders about the weigh-stations, but as my now-partner in crime pointed out, what was the point of stopping if we didn’t have registration papers? We'd only find ourselves attempting to explain the inexplicable to yet another Idaho state functionary who could turn out to be less sympathetic than the trooper. Just how heavy the resulting shit-rain might be was unknowable, but neither of us wanted to find out.

There was only one logical course of action: make a run for the border.

It wasn't much of a "run" at 55 miles per hour (as fast as our absurdly overloaded truck would go), but the next few hours passed without incident. Having stashed the whiskey and white crosses in a less obvious hiding place, we rolled along looking at the world through that cracked windshield, managing to make it across the Utah border by late afternoon without stopping at any weigh stations or attracting the attention of the Idaho police.

Having made our escape, we both relaxed. I pulled out and passed a beer truck -- the only vehicle on the road slower than us -- but the driver immediately sped up and pulled even with our cab.

What the hell? Was this clown trying to race?

No. Unlike us, he was pro behind the wheel, which we realized as he frantically pointed towards the back of our truck. My buddy turned to look, and saw smoke.

Uh-oh.

With a wave to the beer truck driver, we pulled over to investigate the source of that smoke, and found the passenger-side wheel hub of the genny glowing bright orange. This was doubtless due to the six hundred feet of 4/0 we’d figure-eighted and tied-off on that side of the plant -- a great idea while were doing multiple location moves during the shoot days in Sun Valley, but not good for the long drive back to LA. Being greener than fresh spring grass, it never occurred to either of us that an additional six hundred pounds atop a single-axel wheel might create a problem, so now we were out in the middle of nowhere with a melted bearing and daylight rapidly slipping away.

The first thing to do was get that cable off, so we strung it out and wrapped six hundred feet of cold, stiff 4/0 as the sun sank lower in the west. We'd barely finished shoe-horning those six heavy coils into the back of the truck when a Utah Highway Patrol car pulled up. Fortunately, the patrolman didn't ask for our registration, and once he understood the situation, put in a call to a guy who could get us back on the road. A heavy duty pickup truck arrived twenty minutes later with what looked like a fully-equipped machine shop in the bed. It took half an hour and the help of an acetylene torch, but the mechanic installed a new bearing and left us with a warning to take it easy.

"She's pretty stiff," he said, "but ought to make it to LA. That axle's gonna need some serious work once you get there, though."

We thanked him and handed over a hundred dollars cash, then climbed back in the cab and got underway.

Darkness was falling, and we had more than six hundred miles to go.