"You wanna join the union? Get the fuck outta here!"

I've said this before and will keep saying it every month: Blood, Sweat, and Tedium has moved operations over to Substack, where you'll find a reworked post from the archives every Sunday along with the usual first Sunday of the month post. Blogger has just become too glitchy to deal with anymore -- it's a serious pain in the ass -- and once the book is out (hopefully late this summer) I'll close up shop here. This BS&T archive will remain, but no new posts will appear ... so come on over to Substack, where the water's fine. You don't have to "subscribe" -- although that's free -- but if you do, each new post will land in your e-mail inbox.

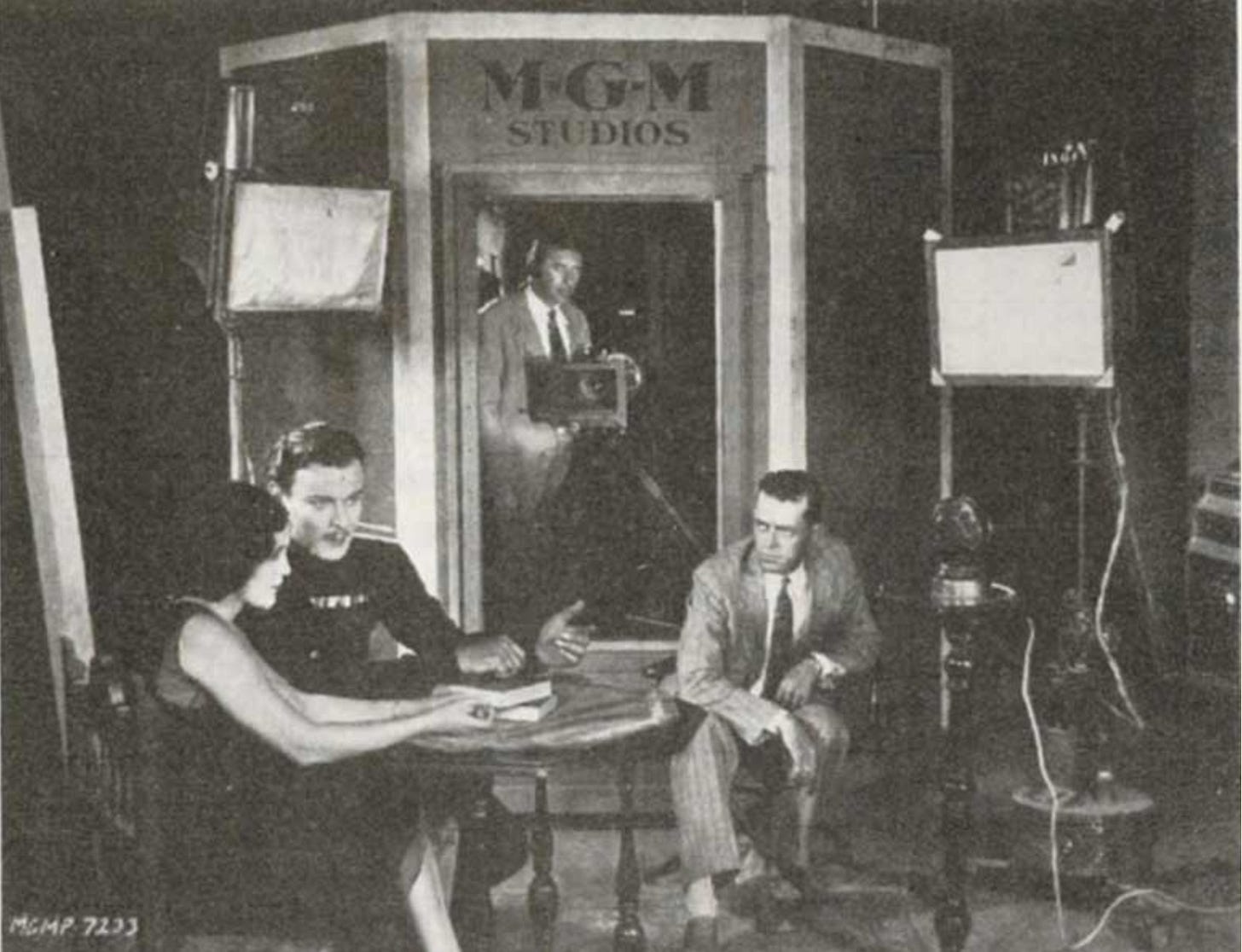

I landed in Hollywood a young man on a mission back in 1977, but it didn’t take long to realize what a steep climb lay ahead in my effort to break into the film industry. Insiders — the sons and daughters of film industry pros — knew the ropes, but with no internet, film blogs, or other guideposts to show the way, most outsiders came in blind, with no idea where to start. After a few months of spending down my savings while staring at the late summer smog, a tip landed my first PA job — unpaid, of course — which eventually led to more work. Once I’d cobbled together a bit of on-the-job experience, I walked into the office of Local 728 (Set Lighting) with a friend to ask about joining the union … at which point the fat, balding guy behind the desk — who was smoking a cigar and wearing a white wife-beater — laughed us right back out onto the street.

“Screw it,” I figured, “I’ll work non-union,” and that’s what I did.

In time I learned more about the process of joining the union, which sounded simple enough: just work thirty union days in a 12 month period for one production company or studio, then pay an initiation fee, and presto, I’d have a union card from a Hollywood IATSE local. But as usual, the devil was in the details: those union work days were guarded by a serious Catch-22. Under normal circumstances, I couldn’t work a union job without being a member of the union, but couldn’t become a union member without working thirty days on union jobs.

In other words, mission impossible. *

It was hard enough for sons and daughters of long-time union members to get a card back then, let alone an outsider with no industry connections. As the years passed, one thing led to another until circumstances aligned to deliver me a 728 card, but it took a very long time. Still, the payoff was having a health plan, union protection on set regarding meal breaks, meal penalties, and overtime, and eventually a modest pension in retirement. How modest, you might ask? Without getting specific, let’s just say that when adjusted for inflation, my monthly retirement allotment is roughly half of the bi-weekly unemployment checks I received between jobs back in the 80s. So … not much. If it wasn’t for the tender mercies of Social Security — and the fact that I managed to buy a small shack in the woods back in the Before Times when cost of real estate hadn’t yet blown through the roof — I might be living in a cardboard condo under the Sixth Street bridge on the concrete banks of the LA River with the rest of the unwashed, unhoused, and unwanted.

Although I was definitely pissed at the IA’s exclusionary policy back in the day, I understood it. To keep their dues-paying members working, the Hollywood locals put a lid on the number of new members allowed in: the last thing they wanted was to dilute the existing pool of work by allowing a flood of new people to join.

Like most organizations run by humans, unions are often plagued by corruption of one sort or another, but they represent the best and only hope for workers to push back against employers who would otherwise abuse and exploit them to the hilt. In a perfect world where all business owners were far-sighted, humane, and understood the mutual benefits of treating their workers well, unions wouldn’t be necessary … but we don’t live in such a world, and I suspect we never will.

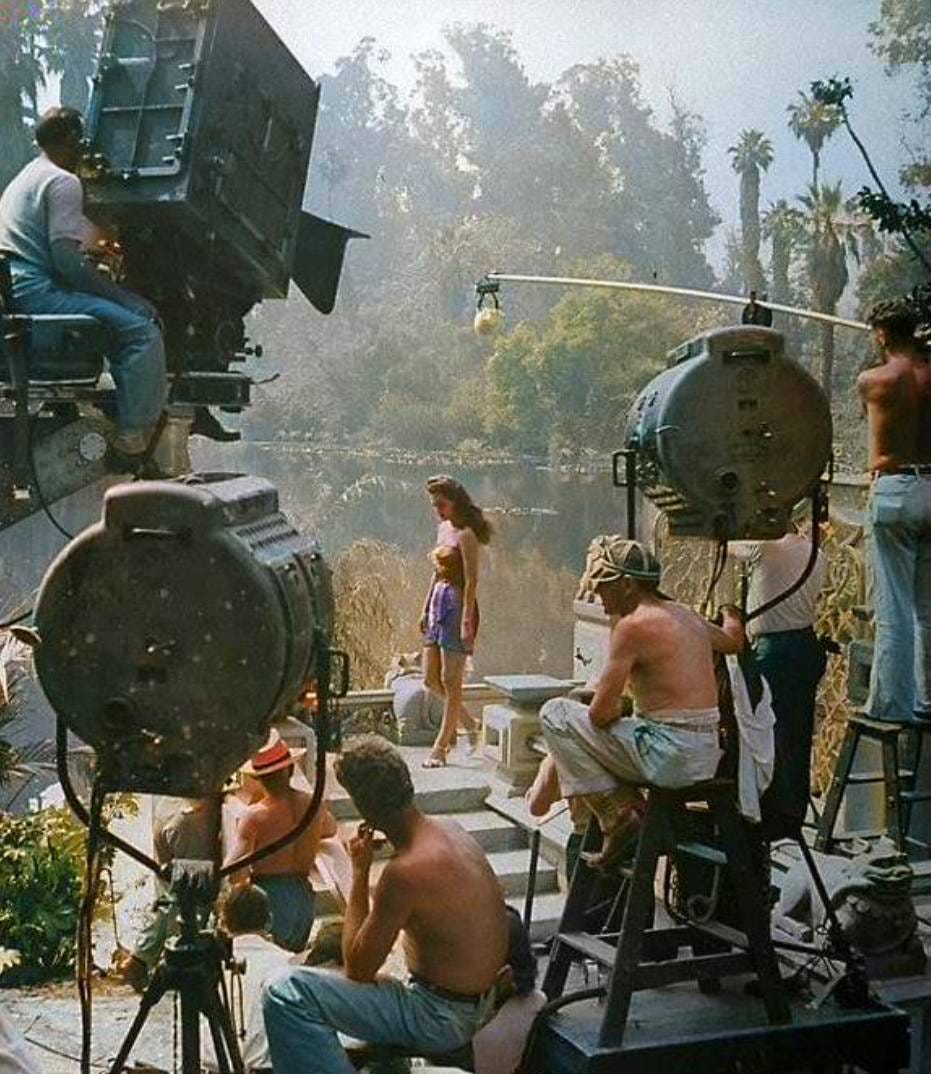

Although unions are a good thing, I have to wonder about a proposal to form a PA union that’s making the rounds of social media these days. Granted, the lot of a Production Assistant is undeniably grim, which I learned firsthand doing two features as a PA back very early in my Hollywood adventure. Tenuously perched on the lowest, most slippery rung of the Hollywood Ladder of Success, a PA works long hours for lousy money doing mundane, boring, thankless tasks on set of in the office. Accorded a minimum of respect, PAs are taken for granted and routinely abused in all sorts of ways — they’re Hollywood’s version of Roman slaves, barely able to afford food and shelter for all their their labor — but just as ancient Rome couldn’t function absent all those slaves, movies and television would not get made without the efforts of PAs.

Most people join a union with the intent of making that craft their career, but there’s the rub: being a PA is such a miserable, underpaid job that the goal of every PA is to get move up the ladder to a position offering more money and respect as soon as possible. Being a PA is a springboard position where a young person gets a good down-and-dirty look at the reality of the film industry while deciding which path to follow. Being a PA is not a career — believe me, nobody wants to be a forty-year-old PA — so how would a PA union work? Why would a PA who can barely afford rent and food shell any of their precious income for an initiation fee and dues in a union they’re hell-bent on outgrowing as soon as possible — and without those funds, how would such a union be able to function?

Okay, maybe my aging brain has been flattened and dulled by too many years of long hours and heavy lifting on set — or too many years of life on earth — but the only way a PA union makes sense to me is if the DGA were to make “Production Assistant” a DGA position as some kind of trainee. The DGA already has a trainee program for wannabe Assistant Directors who might — or might not — have ambitions to move up to directing someday. Having a DGA/PA guild card could offer PAs some protection from being abused and establish a minimum pay scale … but I really wonder if the DGA would have any real interest in tackling this.

I dunno, but if any of you have some thoughts on this, let me know. I’m all ears.

*************************************************

So, it turns out that PA Bootcamp — classes that teach brand newbies the basics of working on set as a PA — is still in action. I first heard about it a dozen or so years ago when there was considerable sturm und drang on the internet as to whether the course offered a valuable service worth the money or if those who ran it were taking advantage of gullible young Hollywood wannabes.

I didn’t know then and I don’t know now — some things never change. Although it’s true that being a PA is neither rocket surgery nor brain science, walking on a working set for the first time with no clue as to the hierarchy or protocols — little but important things like proper walkie-talkie etiquette — is a high stress experience. A little knowledge can go a long way toward easing the confusion, so … I dunno. The idea was to “fake it ’til you make it” when I got started, but there was a lot more production going on in Hollywood back then. With all that activity and churn, it wasn’t quite so hard for a brand-newbie — a stranger in a strange land — to be offered enough slack to learn on the job. Today’s work environment is a lot less forgiving, so being able to act like you know what you’re doing on set could be an advantage for someone just starting out. I don’t know what PA Bootcamp charges or if it’s worth the money, but if I was new in Hollywood and desperate to get some traction, I’d take a look at their website and give it some thought.

The way things are nowadays, I wouldn’t advise any young person to consider a film industry career. Maybe things will improve and maybe not — nobody knows at the moment — but if you’re determined to tilt at the windmills of Hollywood, you’ll want every edge you can get.

That’s all I’m saying.

* There were two ways to get your 30 days: work as a “permit” when Hollywood was so busy that all the union members were working — at which point the studios could hire off the street — but this only happened twice a year, during pilot season in spring and mid-summer when all the TV shows geared up for a new season and features were going strong. The other way was to work a non-union feature that “turned” — signed a union contract during the course of production — so that each day of work then counted as a union day.