(Photo by Robert Aasness)

Yeah, I know ... this is actually the last Sunday in December, not the first Sunday of January, so why is the monthly BS&T post appearing today? Hey, rules were made to be broken, and besides, it's New Year's Eve. I can't think of a better time to offer one last Hollywood air-kiss to 2023 while bracing myself for what's coming in the New Year.

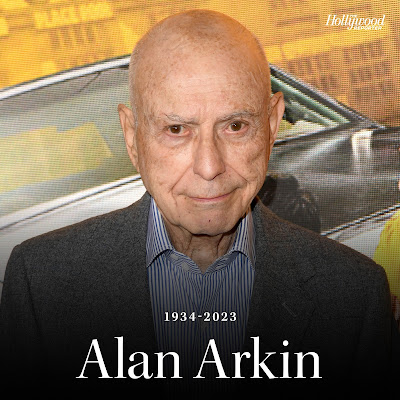

Although I may be one of the few sentient beings in this country who’s never seen a single episode of Homicide: Life on the Street — and likewise missed the entirety of Brooklyn Nine-Nine despite the fact that it was shot on a soundstage just a few yards across the alley at CBS Radford from the stage where I toiled on the longest running show of my so-called career— I was stunned and deeply saddened to learn of Andre Braugher’s entirely premature death last month. 2023 was a rough year for those who appreciate good actors of all stripes. The list of those left us is long and painful, and although there’s no way to determine which of these artists represented the greatest loss (and why the fuck would anybody even attempt such a ghoulish task?), it’s often the most recent losses that sting the most, and such is the case with Andre Braugher.

I first became aware of him in the 2007 sci-fi thriller/horror film The Mist, a taut, spooky, and ultimately bleak film that made quite an impression on me, but I didn’t see him again until Men of a Certain Age came to my television a couple of years later. Braugher gave strong, nuanced, memorable performances in each of these productions, which marked him as an actor to watch. You can get an inkling of how broad was his thespian range and what kind of guy he was from an interview that was broadcast on NPR, but for a measure of the man himself, it's hard to beat this story from a dolly grip who worked with him a long time ago.*

"About 25 years ago I did a movie with him (don't remember the name). I'd gotten divorced a year earlier, and with a small daughter, still didn't have a lot of money. I took a date to the wrap party, a young lady that I wanted to impress. We stopped for drinks at a restaurant on the way, and there was Andre at the bar. I said hi and we chatted for a minute. My date said she liked whiskey, so I told the bartender to give me his best two shots. After we downed them, he said "That'll be sixty dollars."

This was way more than I could afford -- I was expecting maybe twenty bucks ... in 1998 dollars. Andre must have seen the panic on my face, and without missing a beat he told the bartender 'I've got this one."

"Thank you,' I mouthed."

"Forget it,' he said, then wished us a good evening. I've never forgotten this small act of kindness. He was a good man."

Andre Braugher: a wonderful actor and an even better man.

RIP

*************************************************

Anybody who's been watching Slow Horses on Apple TV knows what an entertaining show it is, and that the lead is a role Gary Oldman was absolutely born to play. It's been a long time since Oldman's birth, of course, and the weight of all those years is evident in everything about the slovenly leader of a motley crew of disgraced MI 5 agents -- slow horses -- each of whom has been shunted off to perform menial and meaningless bureaucratic busy-work under the relentlessly critical eye of seasoned veteran and fellow disgracee Jackson Lamb.**

As this piece from GQ notes, the show provides Oldman the opportunity to release and "embrace his inner crank" and let the bile flow while guiding his younger agents through the labyrinth of spy-craft at the price of occasional blood. As usual with Brit shows, the acting of the entire cast is terrific. Slow Horses is a fun show now in its third season, and if you're not watching it, you're missing out.

***************************************************

I've long thought of Frank Capra's classic It's a Wonderful Life as a Christmas Noir: a film that takes its protagonist -- a good man so thoroughly disillusioned by the cumulative weight of fate and circumstance that he's driven to commit suicide, but is saved at the last second by a guardian angel who then shows him how miserable the lives of those he loves would have been had he never been born. It's a truly great movie, but I never thought much past that thumbnail description for one reason: analytical dissections of cinematic classics was never -- ever -- in my wheelhouse. If it was, maybe I'd have spent a forty-year career doing something less strenuous and bruising than wrangling heavy cable and lamps on set in Hollywood. Still, I enjoy reading the analysis of those who do the mental heavy-lifting my brain can't handle, as in this take on Capra's movie from Mick LaSalle, senior film critic for the San Francisco Chronicle.

"This movie was considered too downbeat for audiences when it debuted in 1946, and today is misremembered as a sentimental Christmas classic. The truth is somewhere in between. It's a Christmas movie, in a sense, but it's one that mostly addresses a central question that people ask themselves throughout their lives. The question starts out as "Will my life amount to anything?" Then it's rephrased over time: "Is my life amounting to anything?" "Has my life amounted to anything?" Finally, it's "Did my life amount to anything?"

"Jimmy Stewart, a specialist in screen anguish, plays a man who's convinced that his life has amounted to absolutely nothing, and it takes a divine intervention to make him see otherwise. The redemption of his spirit is reassuring, not just to him, but to all of us. The movie tells us that Christmas is a time of renewal, but says it in a way that's unexpectedly visceral and personal. Our relief for him is relief for ourselves. This is a great American movie about the meaning of success."

"You know you want to see it again. So see it."

Thanks, Mick. I think I will.

***************************************************

As the New Year approached, I had the feeling of being strapped into a roller coaster as it slowly clanked up through the darkness towards the first and highest peak, after which will come a stomach-churning vertiginous plunge into the twisty unknown at an ever-accelerating and increasingly lethal pace. Should anything go wrong -- a worn-out bearing, loose bolt, or broken piece of track -- the entire train of cars could hurtle into the void, sending all the passengers to oblivion. A lot can go wrong over the course of this year, and here we are, just beginning to feel the heart-stopping panic as gravity takes charge ... and it hits us that we're suddenly no longer in control.

What will happen, and what kind of world will we face a year from today? I don't know, but I find it hard to be optimistic these days.

All of this put me in mind of W. B. Yeats famous poem The Second Coming, which feels disturbingly appropriate for our current cultural, political, and geopolitical situation.

The Second Coming

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer:

Things fall apart; the center cannot hold:

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned:

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Surely some revelation is at hand:

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight somewhere in the sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again: but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come 'round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

On that somber note, I wish you all a Happy New Year -- and good luck. We're all gonna need it.

* That would be "D" of Dollygrippery fame, of course. Thanks for sharing your great story, D!

** If "disgracee" isn't a real word ... well, it should be.