"For of all sad words of tongue or pen, The saddest are these: 'It might have been!'

From Maud Muller, by John Geenleaf Whittier

I've never been a fan of daytime television, probably because my family didn't get a TV until I was seven or eight years old, when we were gifted a hand-me-down black and white set that was only used at night -- and my parents decided what we'd watch. When I wanted to see the weekly broadcast of Chillers from Science Fiction, I'd sneak downstairs very late -- on a school night -- while the rest of the house was sound asleep, then turn the volume way down to avoid detection while sitting very close to the screen mesmerized by movies like The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. Until the Kennedy assassination and its grim aftermath -- day after day of news coverage, Oswald being captured and shot on camera, the funeral and procession through Washington DC -- our television was never on during daylight hours. This was hardly something to celebrate, though ... it was the first time I ever saw my dad cry.

During my college years, marooned at home for the summer with a badly broken leg thanks to a very poor decision while riding a motorcycle, I finally succumbed to the lure of daytime TV. Every day I'd hobble up the stairs on crutches (my parents had downsized to a smaller house) to have lunch while my mom watched her favorite soap operas. Of course I thought they were ridiculous -- they were and are -- but after sneering at them for a couple of weeks I began to follow the various melodramatic storylines. Months later, when I came home from school for the Christmas break, mom would fill me in on what had happened. It was rare bit of mother/son bonding, and although I still thought soaps were ridiculous, I'd come to understand that they really do fill a need for many people.

Besides, who am I to judge? People like what they like, and that's their business, not mine.

Cut to thirty-some years later, when I'm reporting for work at the studio as the "extra man" on a sitcom called Rodney, starring country music singer Rodney Carrington. I worked quite a bit on that show, which was always a hoot -- Rodney was a good guy, and that lighting crew knew how to have fun on the job. The director was still rehearsing the cast, so I tiptoed into the set lighting office to find my two fellow juicers howling with laughter at the antics of some guy named "Jerry Springer" on the gold room TV. Curious as to what this was all about, I sat down to watch in slack-jawed astonishment as one guest after another sat before the cameras confessing to every imaginable sexual indiscretion: husbands having sex with their mothers-in-law, wives having sex with their next-door neighbors, and a series of unwed mothers who had no idea which of the many men Jerry brought on stage might be the father of their baby. I'd grown up out in the sticks milking goats and feeding our cows, so the Sodom and Gomorrah of the apparently sex-crazed cities and suburbs represented a side of America foreign to me.

Although it was entertaining in a bizarre, carnival-attraction way, I felt somehow unclean for sharing in the spectacle, and it took me a while to understand what was most bothersome: that these people were so open in sharing their peccadilloes on a national television broadcast, or that I was laughing just as hard as everybody else. It was both, really. Although many among us have strayed into the danger zone of extra-marital liaisons at one time or another, I don't know anybody who'd proudly confess their sins on TV to a live, hooting audience.

Soon the rehearsals were over, so we strapped on our tool belts and got to work, but I now knew about Jerry Springer, and I was not impressed. He was just another amoral manipulative huckster egging on the rubes to humiliate themselves in public, proving that some people really will do anything for money.

So imagine my surprise a few years later when a radio show called This American Life ran a thirty-minute segment describing how Jerry Springer came to be a television carnival barker -- but more to the point, what he could have been, and very nearly was. Truth be told, the story blew my mind. Everybody's heard the Cliff Notes version by now: a young city councilman in Ohio who was dumb enough to pay for the services of a prostitute with a check, ending his political career -- then suddenly he's hosting The Jerry Springer Show. It turns out there's a lot more to this story, which is in equal measure fascinating and sad. I won't say anything more here -- no spoilers from me -- other than to urge you to find a spare half hour, then sit down and listen. It really is an astonishing story.

And hey, you've got time to burn now that the strike is on, so give it a listen.

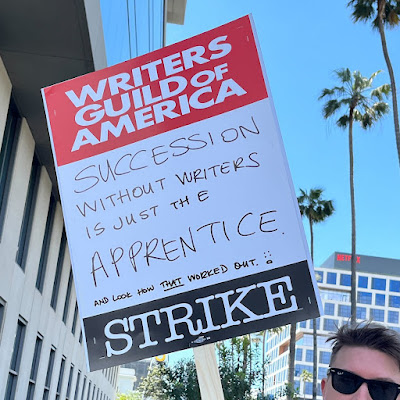

Speaking of the strike: pickets are now walking the studio gates, and the battle is joined. We've been down this road before, and it's not a path anybody wants to travel, especially below-the-line workers who feel a deep and foreboding resonance with the ancient proverb: "When elephants fight, the grass is trampled." Then as now, the crews who do the heavy lifting on set -- grip and electric, camera, sound, set dec, props, hair and makeup, ADs, PAs, stand-ins, locations, and post-production -- are the grass. Directors and the cast of shows suddenly dead in the water are paid well enough that they'll be fine for a while, but the ranks of working actors and hundreds of extras who face a constant struggle to make a living in Hollywood will suffer along with the rest. There's not enough lipstick in Max Factor's massive inventory to beautify this pig of a strike, because it's ugly all the way through. That said, I supported the WGA back in 2007 when I was among the collateral damage of their strike, and I support them now.

Mary McNamara wrote a good piece for the LA Times last week describing the reasons for and importance of this strike, including what struck me as the money quote:

"Streaming exists only because television became a wonder of the modern world. And that happened because it drew some of the most talented, visionary writers and offered them a chance to tell the best stories they could."

True, that. Ever since The Sopranos, The Wire, and Breaking Bad turned the television industry on its ear, working in prestige television (read: cable) became a fever-dream destination for writers who'd yearned to tell the kind of stories broadcast network shows could only dream of, and thus began a second Golden Age of TV. Then came the streamers, eager to harness their slick "new media" technology to the horse-drawn buggy of cable, and they were off to the races. Now that streamers are ubiquitous, the quality of their shows has begun to dim along with their stock prices, because it's not easy to make brilliant television and fat profits via streaming. It turns out that the old dumbed-down advertising-based economic model of broadcast television generated more money for everyone, including the writers. You'll have to look elsewhere for the down-and-dirty details of how residuals were slashed by the streamers (that kind of money-talk makes my eyes roll back in my head) but there's plenty of discussion on the web for anyone interested. The bottom line is this: residuals have long provided an income for writers to keep going during fallow periods between jobs, and with streaming becoming ever more dominant in television, you don't have to be a WGA member to read the writing on the wall. If they don't make a stand now, their future is grim.

Or course, the future for many in the WGA is likely grim anyway. The glut of programming over the past decade -- labeled "Peak TV" by much smarter people than me -- provided jobs for a lot of new writers. That was great, but the problem with a boom-and-bust industry is that the booms never last, and with streamers trimming their expenditures, many of those new writers will find work very hard to find as the rivers of production shrink. Although another boom is likely at some point in the future, this is where the ugly specter of AI raises its digital head. The technology is advancing so rapidly that it's not unreasonable to wonder if in five years or so AI will be routinely blueprinting plots and story arcs for much of television, or even writing complete, cogent, filmable scripts. Prestige shows will probably need skilled human writers for a long time -- the really good stuff needs a human touch -- but with so many shows essentially formulaic, advanced AI may be able to much of the writing. If that happens, the need for a well-staffed writers' room on many shows could vanish into the digital ether.

This is what the WGA is up against, and it's a serious threat. If they're stubborn enough, they can probably beat the producers on the residual issue, but holding back the rising tides of any rapidly advancing technology has always been a steep mountain to climb.

How long the strike will last is anybody's guess, but the one thing we know is that if it doesn't settle soon -- and thus far there's no sign of movement -- a lot of people in Hollywood and beyond will be badly hurt. There's no way to put a smile on this situation, because it well and truly sucks.

For any non-WGA crew people in the LA area who want to show their support on a picket line, here's some information.

Good luck, Hollywood. I'm pulling for you.